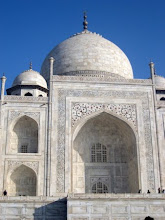

The central focus of the complex is the tomb. This large, white marble structure stands on a square plinth and consists of a symmetrical building with an iwan (an arch-shaped doorway) topped by a large dome and finial. Like most Mughal tombs, the basic elements are Persian in origin. The base structure is essentially a large, multi-chambered cube with chamfered corners, forming an unequal octagon that is approximately 55 metres (180 ft) on each of the four long sides. On each of these sides, a massive pishtaq or vaulted archway, frames the iwan with two similarly shaped, arched balconies stacked on either side. This motif of stacked pishtaqs is replicated on the chamfered corner areas, making the design completely symmetrical on all sides of the building. Four minarets frame the tomb, one at each corner of the plinth facing the chamfered corners. The main chamber houses the false sarcophagi of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan; the actual graves are at a lower level.

The marble dome that surmounts the tomb is the most spectacular feature. Its height of around 35 metres (115 ft) is about the same as the length of the base, and is accentuated as it sits on a cylindrical "drum" which is roughly 7 metres (23 ft) high. Because of its shape, the dome is often called an onion dome or amrud (guava dome). The top is decorated with a lotus design, which also serves to accentuate its height. The shape of the dome is emphasised by four smaller domed chattris (kiosks) placed at its corners, which replicate the onion shape of the main dome. Their columned bases open through the roof of the tomb and provide light to the interior. Tall decorative spires (guldastas) extend from edges of base walls, and provide visual emphasis to the height of the dome. The lotus motif is repeated on both the chattris and guldastas. The dome and chattris are topped by a gilded finial, which mixes traditional Persian and Hindu decorative elements.

The main finial was originally made of gold but was replaced by a copy made of gilded bronze in the early 19th century. This feature provides a clear example of integration of traditional Persian and Hindu decorative elements. The finial is topped by a moon, a typical Islamic motif whose horns point heavenward. Because of its placement on the main spire, the horns of the moon and the finial point combine to create a trident shape, reminiscent of traditional Hindu symbols of Shiva.

The minarets, which are each more than 40 metres (130 ft) tall, display the designer's penchant for symmetry. They were designed as working minarets — a traditional element of mosques, used by the muezzin to call the Islamic faithful to prayer. Each minaret is effectively divided into three equal parts by two working balconies that ring the tower. At the top of the tower is a final balcony surmounted by a chattri that mirrors the design of those on the tomb. The chattris all share the same decorative elements of a lotus design topped by a gilded finial. The minarets were constructed slightly outside of the plinth so that, in the event of collapse, (a typical occurrence with many tall constructions of the period) the material from the towers would tend to fall away from the tomb.